‘Retirement isn’t on my agenda’ — the continuing adventures of collector Robert Chang

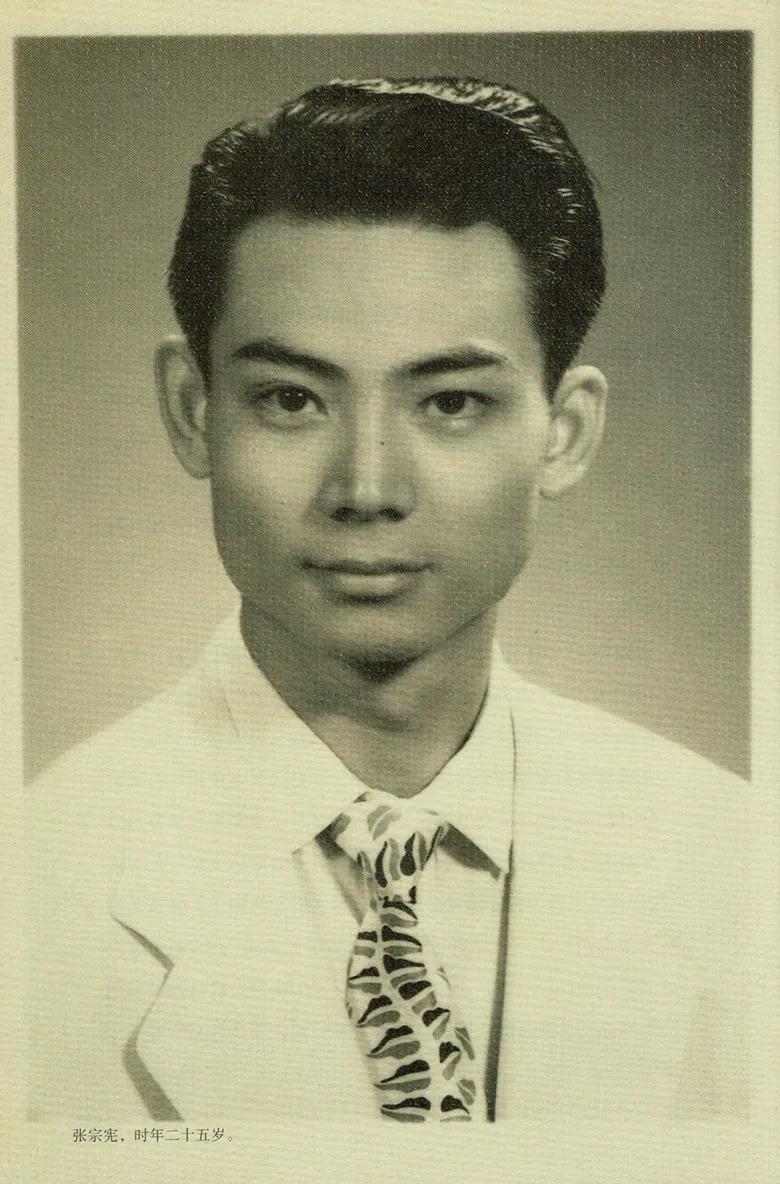

As the legendary dealer and collector turns 95, we look back at his stellar career and talk to him about his future plans

This year marks Robert Chang’s 95th birthday — an impressive milestone in its own right, but even more so when one considers he has spent more than 70 years of his career buying art. As the illustrious collector-dealer makes clear in a new video interview with Christie’s, he has no plans of slowing down.

‘Retirement isn’t on my agenda,’ he says. ‘I’m going to work till the day I drop… As long as there’s something I fancy — and can afford — I’m still determined to acquire it. Even if I were 150 years old, I’d feel compelled to buy it.’

Born in Shanghai in the heyday of the 1920s, Chang opened a department store in his teens before quitting for Hong Kong in 1948 during the Chinese Civil War. He was alone, his beloved elder sister having accompanied him to the ship to say farewell. Tragically, she would die of consumption soon afterwards.

Chang arrived in Hong Kong lacking academic qualifications and carrying with him just a suitcase and $24 in his pocket. Initially, he survived on one or two meals a day and took to sleeping on the streets on used newspapers, when he couldn’t afford lodgings.

‘I had no friends, no family and no money,’ he says. ‘Nor any English or Cantonese.’ What Chang did have, though, was a can-do attitude and a father who could help kick-start his career from afar. A respected antiques dealer in Shanghai, Chang Senior sent his son a consistent supply of objects to sell from his stall in Cat Street Market.

‘My father was my teacher and my inspiration,’ Chang says. ‘I grew up surrounded by his art and antiques… I learned a lot from him, especially through our correspondence [after my leaving Shanghai]’. Along with the pieces themselves, Chang’s father sent him accompanying notes explaining why they were important and what prices should be asked.

Unfortunately, father and son wouldn’t see each other again after the latter’s move to Hong Kong. In fact, they only ever spoke once on phone before the former’s death in the 1960s. What does Chang think his father would have made of his triumphant career?

‘I think he’d have been surprised. He never imagined that I would continue his business, let alone travel the world — as I went on to do — acquiring the finest and most valuable objects around.’

Not long after setting up on Cat Street, Chang became a major broker between Hong Kong and Taiwan. As he started making money, and as his appreciation of antiques increased, he began to build a collection of his own — particularly in ceramics.

It was an excellent time to do so. And by ‘excellent’, read ‘cheap’. As Chang told the Wall Street Journal in 2003, ‘a big Tang Dynasty figurine, now worth several thousands of dollars, would sell [in the 1950s] for about $20.’

Where British and American collectors had dominated the Chinese antiquities market in the first half of the 20th Century, Chang — along with peers such as T. Y. Chao, J.M. Hu, K. S. Lo and E. T. Chow — was one of a few Chinese collectors who helped turn Hong Kong into a hub in the second half of the 20th Century.

Wealth flowed into the city at an ever-increasing rate, thanks to the boom of its commercial, financial and manufacturing sectors.

In the 1950s, Chang was, in his own words, ‘dancing in ballrooms and drinking Champagne every night’. By the 1960s, he was running five stores and had become the golden boy of the Chinese art and antiquities trade.

He says a key to his success has been ‘a willingness to learn’. He has never stopped looking to improve his knowledge — whether that means reading books, talking to other experts, or travelling the world to see art in auctions and museums. That willingness to learn should be seen as symptomatic of both a passion for his subject and a deep-rooted work ethic.

The traditional way of doing business in Hong Kong had been private transactions between dealer and collector. Chang would help usher in a complex new marketplace: he was instrumental in encouraging the major auction houses to set up in the city. Christie’s opened its doors in Hong Kong in January 1986, providing the Chinese art market with a new platform there for growth and maturity.

Chang and Christie’s have developed a close relationship in the intervening 35 years. His porcelain and paintings have been a large source of consignments (Chang’s collecting interest turned to the latter slightly later in his career, with a focus on modern masters such as Zhang Daqian, Xu Beihong and Qi Baishi).

In June 1993, An Exhibition of Important Chinese Ceramics from the Robert Chang Collection, was held for a fortnight at Christie’s London headquarters on King Street. Building on the international exposure this provided, a trio of sales of Chang’s ceramics followed at Christie’s Hong Kong: in 1999, 2000 and 2006.

Various records were set along the way — including the world-record price for a piece of Qing dynasty porcelain, when an 18th-Century falangcai bowl (depicting two swallows in flight) sold for HK$ 151.3 million/US$ 19.5 million in the final sale.

Chang has bought at countless Christie’s auctions too. What was his favourite purchase?

‘Oh, the tiger vase,’ he says without hesitation. ‘I’ve seen many works of art, but never a piece like that.’ Chang is referring to this spectacular, cloisonné enamel, hu-form vase, beloved by him and his wife in equal measure. (It actually features the face of an ancient mythological creature known as a ‘taotie’ on the front rather than a tiger — but Chang thinks it looks like the latter.)

He went to his first ever auction in London in the late-1960s and hasn’t ceased attending sales since. In the 1990s he was bidding at the inaugural auctions held in Beijing and Shanghai; and as recently as the summer of 2019, Chang bought this Qianglong white jade vase from Christie’s in Paris. The Coronavirus pandemic, he says, marks a pause, rather than an end, to his auction-going. ‘Flying and buying everywhere’ continues to be his motto.

Chang admits to sleepless nights on the eve of sales that excite him. In the sales room itself, he cuts an unmistakeable figure: fond of eye-catching entrances down the central aisle, often sporting sunglasses, a snazzy suit and one of his myriad hats. No auctioneer will wield a gavel before Chang has taken his seat on the front row.

Many of today’s collectors prefer to bid over the phone or online rather than in person. ‘That’s not my way.’ Chang says. ‘I’m Robert Chang — Number one!’ He’s known to enjoy waltzing out of the room to loud applause after a winning bid.

The collecting landscape has changed a great deal since he started out: the days of snapping up masterpiece after masterpiece at bargain prices are over. His watchword for new buyers is ‘patience’. He advises them not to rush into purchases; to ask questions and research first; and to ensure they have the money to buy the best, when it appears on the market.

It’s worth adding that the relationship between Chang and Christie’s extends beyond the auction house. He and the firm’s employees frequently travel together to see art, out of a shared passion rather than with a transaction in mind. Just as they did in 2015, on the trip to Iran mentioned in the video, when they looked at Chinese ceramics (from the Yuan to the early-Ming period) in the National Museum of Iran in Tehran.

Back home, anyone lucky enough to visit one of Chang’s houses might compare the experience to visiting a palace — so packed with treasures are they, from ceiling to floor. His house in Suzhou even boasts a rock garden where the rocks are covered in silver and gold.

Chang, however, has long been an advocate of giving back. ‘I dislike people who forget their past,’ he said in 2006. ‘When you have money, you need to remember the time when you had nothing.’ In recent years, he has donated a selection of works to Suzhou Museum.

He plans to bequeath part of his collection, in equal thirds, to three cities close to his heart: Shanghai; Suzhou (where his parents were from); and Hong Kong (which, he says, provided the platform for his career).

He has other ambitions before that, though. As soon as Covid lockdown restrictions lift and it’s safe to travel again, he plans a trip to Dunhuang in north-west China to see the Buddhist art in the Mogao Caves, as well as works in the collection of the Dunhuang Museum.

‘I can say I’ve reached a stage of my life where I’m content,’ Chang says. ‘But I still have things to do before I say farewell.’